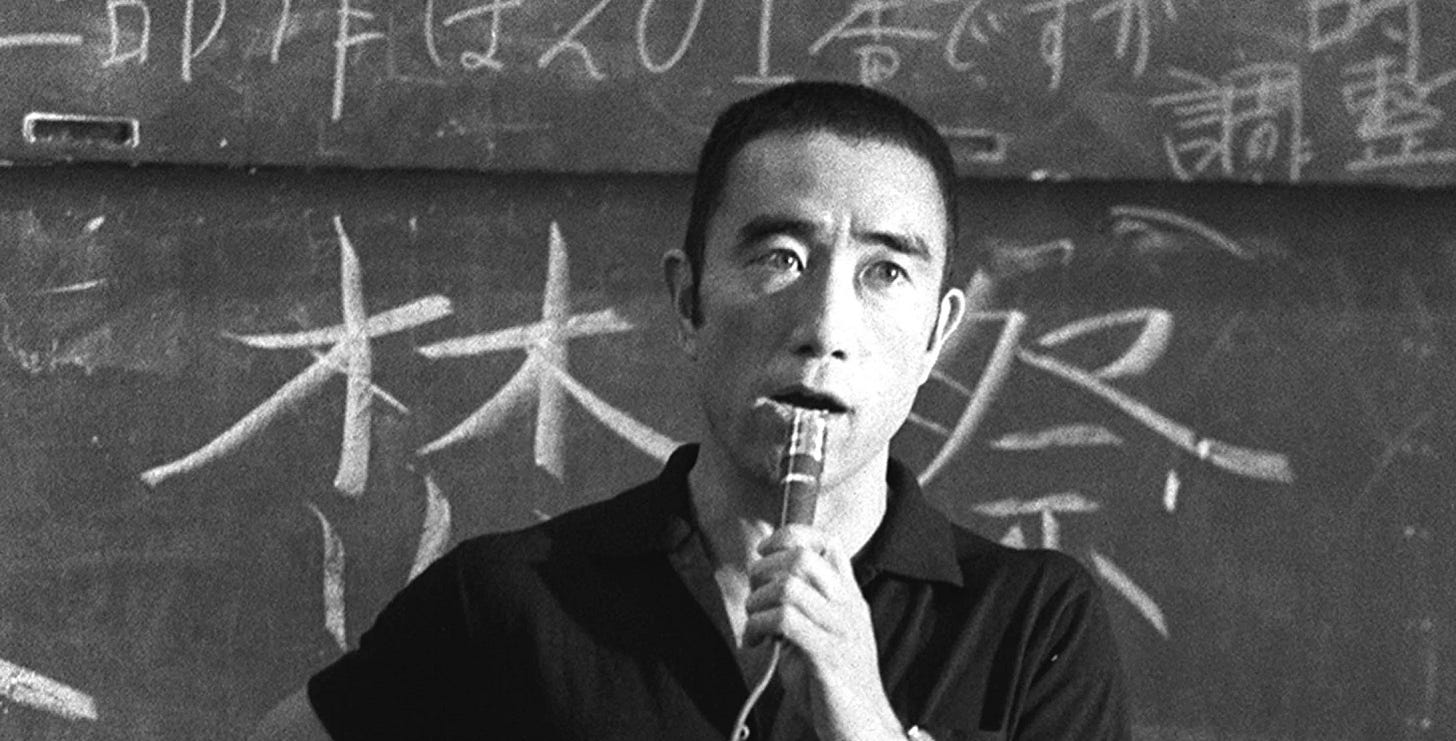

A Japanese author whose literary contributions were last popular in the West during the 1960’s and who committed spectacular ritual suicide, assisted by his male lover and other members of his ultra-nationalistic private militia at the age of 45 in 1970, is suddenly gaining minor interest again. This smattering of interest is perhaps driven foremost by a certain YouTube celebrity, who has publicly declared his interest, but possibly also by a generational shift in internet commentators. The generation first initiated on the internet is now in their late forties and early fifties and going through a crisis of existence. A crisis much like that experienced by the author: Yukio Mishima.

Yukio Mishima was, to say the least, a complex character. A world class author, born in 1925, with books describing his supressed homosexuality, difficult upbringing, nationalism, experiences from the war and his mid-life crisis. His large volume of works came out in post-war Japan during a time of huge societal change and upheaval. His books were widely translated and he was popular in the West as well, but died in 1970 at the height of his career. I will not pester you with the details of Mishima’s life, as I am more interested in discussing the reasons for this resurgence in interest. A few details must be brought up, however.

His views were by any measure “problematic”, to say the least. He was an ultra-nationalist, a self-described misogynist and he advocated for violence. He was also a hypocrite, marrying a wife while also living as a homosexual, he also dated a trans woman, probably cross-dressed on occasion and spoke extensively with far-left activists, sometimes agreeing with them during Japan’s turbulent 1960’s student upheavals.

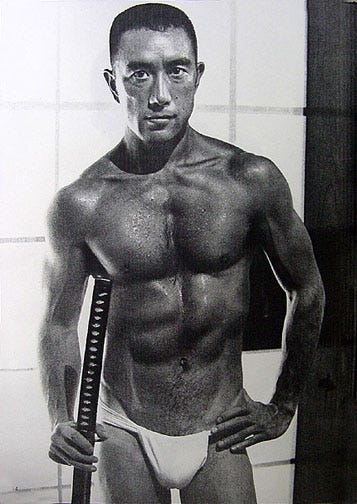

After an incredibly successful literary career, Mishima perceived that rising to the top in literature wasn’t enough. He needed more and thus started working out, became a body builder, dabbled in acting, was granted access to military training and founded a private militia group of like-minded nationalists, that trained with him. The members of said group presumably fawned over the older and wiser Mishima. In his political manifesto, Sun and Steel, explaining himself, he recounts how his life started out with the pen and how he changed that around to be a life of the sword. He was also left with a profound longing for violence, war and conflict. This fascination led to his demise at his own hand.

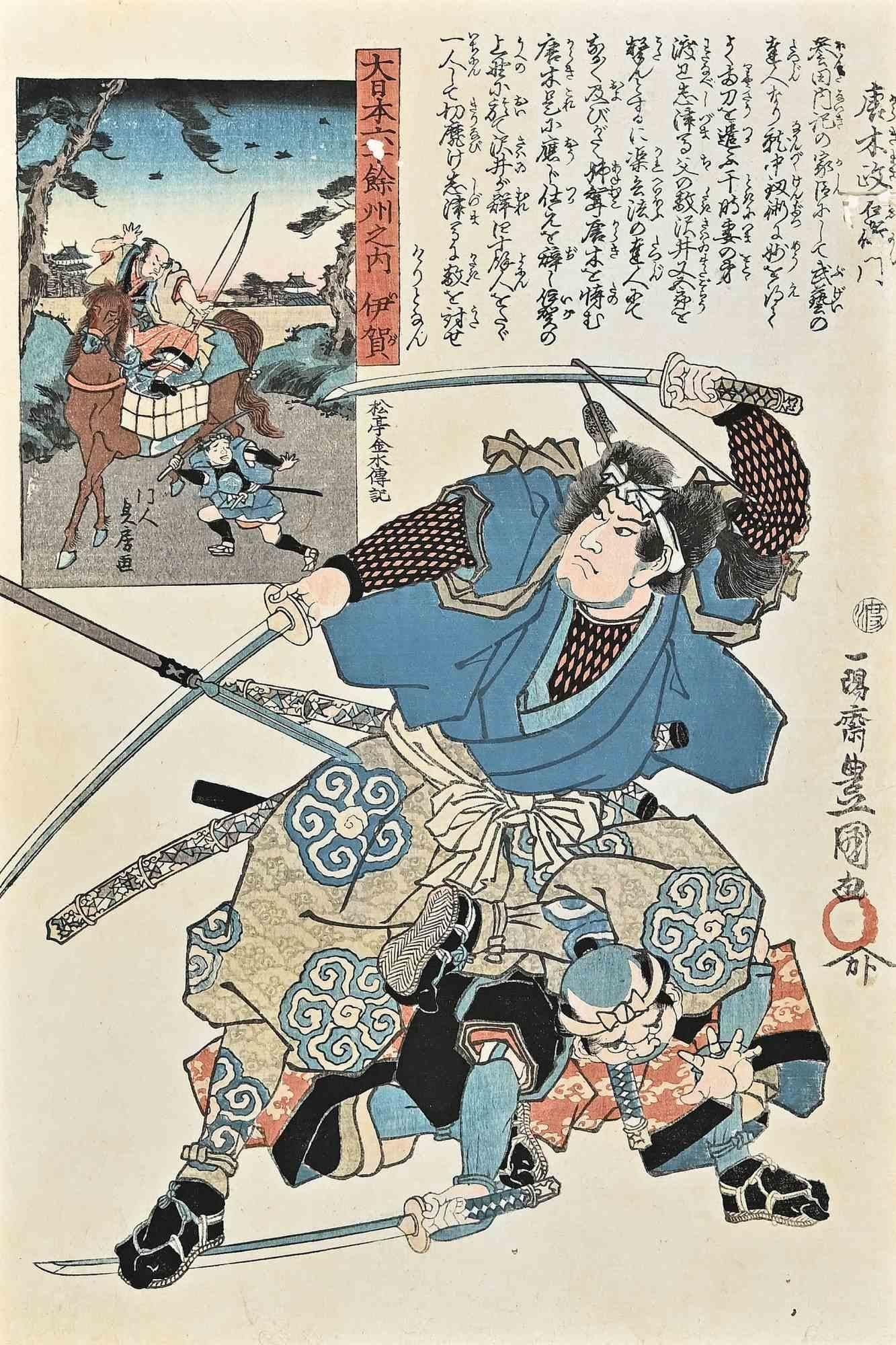

We should also quickly look at Mishima’s belief systems. His views were by any measure “problematic”, to say the least. He was an ultra-nationalist, a self-described misogynist and he advocated for violence. He was also a hypocrite, marrying a wife while also living as a homosexual, he also dated a trans woman, probably cross-dressed on occasion and spoke extensively with far-left activists, sometimes agreeing with them during Japan’s turbulent 1960’s student upheavals. He certainly did not fit any box others might try to place him in. One more intrinsic feature of Mishima’s thought was his obsession with death. This could be construed as something culturally Japanese, and certainly there is an element of that here, harking back to samurai ideology, but it’s also more visceral. Mishima confronted the idea and cultural meaning of death and took it as part of his personality.

Mishima’s struggles and views bring us around to our current modernity and the fascination with this character. Modern times manage somehow to be so far away from the zeitgeist of the 1960’s, yet at the same time societal upheaval, strong opinions a strong sense of impending doom and mass media proliferation are endemic to both time periods. In this atmosphere Mishima became disillusioned by his success and role in society much like middle-aged men are doing right now. Right now, there is a re-orientation in the way Western Man is faced with death. Plague and the great die-off of the baby boomers and perhaps more importantly, the end of an eternal-life ideology perpetrated by the postwar generations, is profoundly affecting the current one. The 1960’s those ideas were going in the opposite direction. After decades of war and disease, society believed in life and a new generation. For Mishima, this felt wrong and we find ourselves in similar circumstances.

People would rather die a violent death doing something meaningful, than live with perpetual ennui. The loss of meaning people in modernist society face daily is soul destroying.

One more point I should make, is that there is ample research that confirms, that people are at their most unhappy between 45 and 55, with a sliding in period in their 30’s. This is the age group that is most interested in Mishima and his message of fitness and being actionable in the physical world and of course this generation is going through a crisis of middle-age.

A mid-life crisis is nothing to laugh at. It might be caricatured as facing only men and being cured by red convertibles or motorcycles, but in reality, it faces both sexes. There is the fact that with regard to interest in Mishima, we are talking about men. Men are faced with many new challenges in this world of today, with a faltering sense of masculinity taking centre stage. The fitness craze feeds into this and works as an outlet for men who have lost a sense of meaning within the non-physical world and culture we live in. For Mishima it was the same: he became scornful of weakness and sought physical fitness instead of intellectualism.

I’ve written before about how people who take part in violent, often traumatising events, such as wars, would not trade places with anyone else. People would rather die a violent death doing something meaningful, than live with perpetual ennui. The loss of meaning people in modernist society face daily is soul destroying. Mishima addressed this, discussing about how he feared and yet did not fear death, both at the same time. He was afraid of dying in a hospital bed overcome with cancer. But was never afraid of a violent, even painful death. He much preferred the latter. As modern man, Mishima was frustrated with this. Frustrated to the extent that he ended his life with ritual suicide. Living in a time of peace, he was unable to produce a noble death in any other way.

This crisis of Man has manifested itself as interest in nationalism, misogyny and philosophers and public speakers advocating it. The feeling of meaninglessness lowers the barrier for men to support political movements and ideas that are at their core, corrupt and destructive to both culture and humanity and work in the service of modernity and industrialism. This can be observed over and over historically: Hitler’s Brownshirts sought out men who were downtrodden by poverty and unemployment and today it is again young men who flock to radical movements.

Being enamoured by mere intellectual pursuits, spending our limited time in this world writing manifestos on the internet or interacting on social media is only of limited use in the big picture. Only by stepping outside and finding avenues of action can we truly change things.

Now for some clarification on my own feelings on these matters: I, F. Faustus advocate for a traditionalist society, that values institutions that preserve a place for everyone in society, works for an ecological, small and limited, agrarian society. This is directly opposed to the kind of fascist industrialism and racist anti-womanism that so-called “traditionalists” in the modern realm advocate for. Naturally both political ideas involve strong notions of nostalgia and a harking back to a “better time” that probably never existed for very long or for everyone. Either way, we need to learn from the past to build a better future, not build the same oppressive and destructive machines over and over again.

I do feel, it is of utmost importance to better ourselves as human beings. Being enamoured by mere intellectual pursuits, spending our limited time in this world writing manifestos on the internet or interacting on social media is only of limited use in the big picture. Only by stepping outside and finding avenues of action can we truly change things. In this sense Mishima was on the right track. Even the highest form of intellect does nothing, if it isn’t translated in to actionable outcomes.

Despite being a far-right nationalist, Mishima didn’t bow to far-right orgs or ideologues, instead he found inspiration from old texts on Samurai traditions. While looking back he also had that very modern quality of the quintessential far rightist; being openly a sex pervert. In this sense, funnily enough, Mishima is an aspirational character. Despite his failings, he is willing to look back and find useful structures from the past to build a better today. He is willing to espouse the written word, something that was core to his being from a very young age and trade it in for physical fitness and all the hard work that requires. He was willing to step out of his comfort zone in his middle age, give up the comfort of a lazy life for danger, action and adventure. He was willing to listen to his own flesh more than ideology and make his own roads.

The fact that Mishima has become aspirational is itself interesting. It tells of deep seated problems in how people find themselves in a society which is quickly walking in to destruction due to climate change and the collapse of human populations to a fraction of it’s size.

Do not kid yourself however, ideologically Yukio Mishima was a clearcut fascist, an intellectually almost tedious one. His political views are as wearisome as his life was interesting. This itself is baffling, as the man was a deep thinker with a touch for complex prose. It makes him even more interesting as a character. It should be noted, that Mishima is more complex and multi-levelled than I can quickly explain in this limited essay. He is a true enigma, baffling those who read about him. Perhaps that’s why almost any mention of him usually descends into a lengthy explanation of his complicated life.

We can learn from Yukio Mishima while acknowledging his failings. Mishima continues to baffle us and at the same time, appeal to our personal sense of crisis. I recommend watching the autobiographical film about his life as a quick introduction to the subject. The director of that film pointed out, that while westerners have the luxury of saying the enigma of Mishima is due to him being Japanese, people in Japan are even more baffled by him.

The fact that Mishima has become aspirational is itself interesting. It tells of deep seated problems in how people find themselves in a society which is quickly walking in to destruction due to climate change and the collapse of human populations to a fraction of it’s size. The crisis of middle-aged man in the midst of this is another footnote in history, that is echoed in people who came before us, such as Yukio Mishima.

Here is the trailer of the excellent Mishima biopic, I recommend watching the movie and is a good starting point on everything Yukio Mishima:

Here is the very interesting interview of Paul Schrader, the director of the Mishima film:

And for those who are looking for more and deeper material on Mishima, here’s an excellent video on him. It is probably the best video on Mishima online. I have a few nitpicks, and I don’t agree with everything, but it is still an excellent video:

AD2024